Beliefs

Children's Ministry

Directions

Favorite Links

Home

Photo

Resources

Salvation

Sermons

As with all things pertaining unto scripture we must look to Acts 17:11

11 Now the Berean Jews were of more noble character than those in Thessalonica,

for they received the message with great eagerness and examined

the Scriptures every day to see if what Paul said was true." NIV

What is Christian apologetics?

The English word “apology” comes from a Greek word which

basically means “to give a defense.” Christian apologetics, then, is the science

of giving a defense of the Christian faith. There are many skeptics who doubt

the existence of God and/or attack belief in the God of the Bible. There are

many critics who attack the inspiration and inerrancy of the Bible. There are

many false teachers who promote false doctrines and deny the key truths of the

Christian faith. The mission of Christian apologetics is to combat these

movements and instead promote the Christian God and Christian truth.

Probably the key verse for Christian apologetics is 1 Peter

3:15, “But in your hearts set apart Christ as Lord. Always be prepared to give

an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you

have. But do this with gentleness and respect...” There is no excuse for a

Christian to be completely unable to defend his or her faith. Every Christian

should be able to give a reasonable presentation of his or her faith in Christ.

No, not every Christian needs to be an expert in apologetics. Every Christian,

though, should know what he believes, why he believes it, how to share it with

others, and how to defend it against lies and attacks.

A second aspect of Christian apologetics that is often

ignored is the second half of 1 Peter 3:15, “but do this with gentleness and

respect...” Defending the Christian faith with apologetics should never involve

being rude, angry, or disrespectful. While practicing Christian apologetics, we

should strive to be strong in our defense and at the same time Christ-like in

our presentation. If we win a debate but turn a person even further away from

Christ by our attitude, we have lost the true purpose of Christian apologetics.

There are two primary methods of Christian apologetics. The

first, commonly known as classical apologetics, involves sharing proofs and

evidences that the Christian message is true. The second, commonly known as

“presuppositional” apologetics, involves confronting the presuppositions

(preconceived ideas, assumptions) behind anti-Christian positions. Proponents of

the two methods of Christian apologetics often debate each other as to which

method is most effective. It would seem to be far more productive to be using

both methods, depending on the person and situation.

Christian apologetics is simply

presenting a reasonable defense of the Christian faith and truth to those who

disagree. Christian apologetics is a necessary aspect of the Christian life. We

are all commanded to be ready and equipped to proclaim the gospel and defend our

faith (Matthew 28:18-20; 1 Peter 3:15). That is the essence of Christian

apologetics.

www.gotquestions.org

Catholic Religion Purposely Taken Out Scripture

Transubstantiation

Catholic Religion Purposely

takes out

one of God's Ten Commandments

They shall go to confusion together that are makers of idols. Isaiah 45:16 Catholics love images

Catholics bow down in front of statues and pray. They love to adore the host which is a piece of bread. They light candles and pray to the dead like it does some good. They also adore relics like a dead monk's head or a dead saint's finger. We also know that they gaze upon other "sacred" objects and images like pictures of a madonna and naked baby Jesus (salvation was accomplished by THE MAN Christ Jesus). Finally we know that they think that there is some benefit of having "a Jesus" hanging on the cross in their homes so they can visualize the object of their worship. Perhaps they think the crucifix is a good luck charm. They will vehemently tell you that they don't worship the images--I've seen a picture of the pope bowing down to Mary.

The Bible says don't even make images

Well, what doth the Bible say about worshipping images? It says much my friends but today we are looking specifically at the Ten Commandments found in Exodus chapter 20. Most of us know that the Ten Commandments prohibit even making images. This poses a problem for the Catholic religion. How does it get around this?

THE CATHOLIC RELIGION CHANGES THE TEN COMMANDMENTS!PLEASE READ THE FOLLOWING STATEMENT. PEOPLE KEEP MISSING IT.

Even their own perverted Bibles have something that approximates the commandment to not make images, but since their leaders tell them they are too spiritually dumb to understand the Bible, they don't read it (or read it with muddy eyeballs). And so, the wicked deceitfully change the ten commandments and PUT THEM IN A BOOK SOMEWHERE OR POST THEM ON A WALL AND TELL THE PEOPLE TO MEMORIZE THEM. Of course people are going to trust their almighty priests to tell them the truth (bad move).

How can they delete a commandment and still have ten?

Some man might ask me, "If the Catholic religion deletes a commandment how do they still come up with ten commandments?

Let's compare the Catholic ten commandments to the real ten commandments from the good ol' King James Bible, that pillar of doctrinal truth (God loves the truth, you know). The following list on the Catholic side is taken from a textbook used in a Catholic school. It is titled, "Growing in Christian Morality" by Julia Ahlers, Barbara Allaire, and Carl Koch, page 40. It has both nihil obstat and imprimatur which are official declarations that a book or pamphlet is free of Catholic doctrinal error. The authors of this book know these commandments are deceitful. Look at what they say:

...These are the Ten Commandments, from Exodus, chapter 20, in the traditional way they are enumerated by Catholics They did NOT use what THEIR NRSV said, they "enumerated" them the traditional way enumerated by Catholics.I'll let you take a look first (see if you can figure out what they deleted) and then I'll explain...

The Catholic Deception* The King James Bible First Commandment I, the LORD, am your God...You shall not have other gods besides me.

First Commandment I am the LORD thy God...Thou shalt have no other gods before me.

Second Commandment You shall not take the name of the LORD, your God, in vain.

Second Commandment Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them.

Third Commandment Remember to keep holy the sabbath day.

Third Commandment Thou shalt not take the name of the LORD thy God in vain.

Fourth Commandment Honor your father and your mother.

Fourth Commandment Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy.

Fifth Commandment You shall not kill.

Fifth Commandment Honor thy father and thy mother.

Sixth Commandment You shall not commit adultery.

Sixth Commandment Thou shalt not kill.

Seventh Commandment You shall not steal.

Seventh Commandment Thou shalt not commit adultery.

Eighth Commandment You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor.

Eighth Commandment Thou shalt not steal.

Ninth Commandment You shall not covet your neighbor's wife.

Ninth Commandment Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour.

Tenth Commandment You shall not covet your neighbor's house.

Tenth Commandment Thou shalt not covet.

Did you see it?

The Catholic religion deletes the second commandment and makes the 10th commandment into two. If you follow them all the way down from the second commandment you'll see the Catholic religion is always one ahead of the King James. Finally at the tenth commandment they break it into two and make it the 9th and 10th commandments. What deception! What deceit! What guile! I tell no lies here--just get out the Bible and compare. They even corrupt their own Bible by deleting the 2nd commandment!

You see the reason the Catholic religion killed people with Bibles is 'cause their deception is just too easy to see in light of God's word. Just a little more mumbo-jumbo gumbo for your consideration...

https://www.jesus-is-lord.com/mary.htm

*taken verbatim from, "Growing in Christian Morality" by Julia Ahlers, Barbara Allaire, and Carl Koch, page 40. It has both nihil obstat and imprimatur which are official declarations that a book or pamphlet is free of Catholic doctrinal error. The authors have used the NRSV--and they've even corrupted the corrupted!What's worse is that the authors of this book know these commandments are deceitful. Look at what they say:

...These are the Ten Commandments, from Exodus, chapter 20, in the traditional way they are enumerated by Catholics:

What do some of the major cults and world religions believe? How do they stack up against the Bible?

The following list gives the names of the major religions and cults and what they believe about God, Jesus Christ, Salvation, Heaven, Hell, and the Scriptures. Click on the name of the cult or religion to find out what it believes.

Find out what the Scriptures say about these topics.

Catholics and Protestants in Conversation

Article by Greg Morse

Staff writer, desiringGod.org

Roman Catholic, Cheap Grace, and Reformed Christian sit

in a small country pub, discussing justification. To the surprise of each, “It

is of grace” they assert, one by one.

Seeing the suspicions written across the faces of the

other two, the Catholic begins, “My catechism reads, ‘Justification comes from

the grace of God.’ And by grace we mean generally, ‘favor, the free and

underserved help that God gives to us to respond to his call to become children

of God, partakers of the divine nature and of eternal life’ (Roman Catholic,

418). We all affirm we are ‘justified by his grace as a gift’” (Romans 3:24).

To undermine any misgivings, he quickly adds, “It also

states as bright as the sun, ‘[N]o one can merit the initial grace of

forgiveness and justification, at the beginning of conversion’ (Roman Catholic,

420). Or, to put it more strongly, ‘If any one shall say, that man may be

justified before God by his own works, whether done through the strength of

human nature, or through the teaching of the law, without the divine grace

through Jesus Christ; let him be anathema’” (Counsel of Trent, Canon I).

Confused, Cheap Grace turns to Reformed Christian,

“Wasn’t one of the pillars of the Reformation Sola gratia — justification by

grace alone? But this fellow says he too believes in justification as undeserved

favor, free and initiated by God. What exactly did our forefathers mean if

Catholics also acknowledge God’s grace justifies?”

How might you answer this question?

By Grace Alone

Talking together at this quaint countryside, the

differences at the surface between Cheap Grace, Roman Catholic, and Reformed

Christian might seem surprisingly thin. Each uses the same words. Each mentions

something about the grace of justification being underserved, the result of

divine — not human — initiative. Each will speak of Jesus and his cross at some

point and stand aligned in condemning human works apart from grace.

In other words, each will say that God redeems and

restores into right relationship with himself by the work of his decisive grace.

Each will say, in their own ways, salvation is of the Lord, and join to sing

“Amazing Grace.” So what is the difference?

To show the relevance of Sola Gratia, a doctrine

rediscovered in the Reformation, consider the contrast between Reformed

Christian’s understanding of by grace alone contrasted first with the Roman

Catholic’s, and then with that of Cheap Grace.

Catholic Versus Reformed

Over the course of their discussion, Roman Catholic and

Reformed Christian discovered they use identical terms but with significantly

different meanings.

JUSTIFICATION

The first impasse is the meaning of justification

itself. When the Catholic catechism states that justification is of grace, he

understands it as “not only the remissions of sins, but also the sanctification

and renewal of the interior man” (1989, emphasis added). Justification, in other

words, includes sanctification and regeneration. Indeed, to the Catholic,

justification embraces “the whole scope of the Christian life” (The Doctrine on

Which the Church Stands or Falls, 744).

Justification, in the Roman conception, is an ongoing

process, rising and falling, being attained by the grace of the sacraments and

possibly lost through a failure of the sinner to persevere in faith and works

and the sacraments of the church. Justification, for the Catholic, concerns what

God continually does in man.

“Justification, for the Protestant, concerns what God

declares over him before he does anything in him.”

Opposed, the Reformed Christian insists that

justification is a “legal act, the declaration of the forgiveness of sin and the

imputation of righteousness.” In fact, the Catholic counsel of Trent, in

response to the Reformation, declared them damned who taught that “men are

justified either by the sole imputation of the righteousness of Christ, or by

the sole remission of sins, to the exclusion of the grace and the charity which

is shed abroad in their hearts by the Holy Ghost [Romans 5:5], and is inherent

in them; or even that the grace, by which we are justified, is only the favor of

God” (Canon xi). Justification, for the Protestant, concerns what God declares

over him, by faith, while the justified is still ungodly (Romans 4:5).

RIGHTEOUSNESS

Second, and related, the two disagree about

“righteousness.” For the Catholic, justifying righteousness is not Christ’s

perfection accredited (that is, imputed) to the sinner’s account. Rather the

Catholic means “the rectitude of divine love.” With justification, he says,

“faith, hope, and charity are poured into our hearts, and obedience to the

divine will is granted to us” (catechism, 1991). And this infusion comes through

the sacrament of Baptism: “Justification is conferred in Baptism, the sacrament

of faith” (1992).

For the Reformers, a different notion of righteousness

was reclaimed — a righteousness revealed in the gospel (Romans 1:17). The good

news is that sinners — dead in their trespasses, sins, and unrighteousness —

can, through faith in Jesus’s perfect life, substitutionary death, and

validating resurrection, have their sins forgiven and Jesus’s own perfect

righteousness counted as theirs by union with him. As was long prophesied, the

Suffering Servant would “make many to be accounted righteous, and he shall bear

their iniquities” (Isaiah 53:11).

Luther distinguished alien righteousness — Christ’s

perfections, outside of us, applied to us legally in justification — and proper

righteousness — our own righteousness worked out as a result. Catholic teaching

combines the two. Paul, however, makes the contrast clear: “Now to the one who

works, his wages are not counted as a gift but as his due. And to the one who

does not work but believes in him who justifies the ungodly, his faith is

counted as righteousness” (Romans 4:4–5). Paul staked his life and eternity on

“the righteousness from God that depends on faith” (Philippians 3:8–9) — a

righteousness that doesn’t foremost make us just but accounts us just in Christ.

GRACE ‘ALONE’

All this leads to the fact that for Roman Catholic,

justification cannot be by grace alone as Reformed Christians understand it.

Catholicism teaches, “Justification establishes cooperation between God’s grace

and man’s freedom” (catechism, 1993). Since justification includes the inherent,

lived-out righteousness of the believer to keep it, “the formal cause of

justification refers both to God and to man” (Doctrine, 743). God enlists humans

as partners in justification. “In the end, eternal life is both a grace promised

and a reward given for good works and merits” (Doctrine, 744).

Lutherans and Catholics of modern times created a Joint

Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification in which they write,

By grace alone, in faith in Christ’s saving work and not

because of any merit on our part, we are accepted by God and receive the Holy

Spirit, who renews our hearts while equipping and calling us to good works.

(article 15)

“For Roman Catholic, justification cannot be by grace

alone as Reformed Christians understand it.”

But what is meant “by grace alone”? Leonardo De Chirco

writes, “For the Catholic Church, ‘by grace alone’ means that grace is

intrinsically, constitutionally, and necessarily linked to the sacrament, to the

church that administers it, and then to the works implemented by it.” Still in

line with Trent, “grace is necessarily sacramental and seen inside a

synergistic, dynamic process of salvation” (Doctrine, 752–753).

This is not “by grace alone” as Luther understood it.

Justification, as Carl Trueman summarizes, places “the believer’s salvation

outside himself, in the action of God. The very fact that justification for

Luther is a declaration of God, a word that comes from the outside, underscores

and intensifies the idea that salvation is all of grace” (Grace Alone, 124).

Reformed Christians, then and now, insist that

justification by grace alone allows no talk of merit. Christ allows no

sidekicks. The Catholic view entails divine grace that is undeserved assistance

to get those “capable of God” going, and stands by through the sacraments of the

church to help collaborate in salvation. The Reformed understands it as the

decisive gifting of perfect righteousness once and for all to those hopelessly

condemned in sin. God becomes 100% for us on the sole basis of Christ’s

righteousness. Then, once he is for us (fully justified), we grow, by the

Spirit, in our own lived-out righteousness. The Catholic view necessitates the

undeserved help of God in salvation; the Reformed view, the unilateral acquittal

and divine pronouncement of “Righteous!” at the first instant of being joined to

Christ by faith.

Reformed Versus Cheap Grace

“I knew it,” Cheap Grace interrupts, relieved.

“Justification is all of grace — grace alone — now until the end! No matter how

I live, no matter what sins I still fall into, the good news of the gospel

states that God sees Jesus when he looks at me. Justified by grace alone!”

“This is the problem with Protestant theology,”

complains Roman Catholic. “It does not take obedience and sin seriously. Does

Paul not charge us to ‘work out your own salvation with fear and trembling’

(Philippians 2:12)? Justification is no license to continue sinning without

consequence.”

It was in response to this that Reformed Christian and

Cheap Grace began to realize deep distinctions between them. After some time,

Reformed Christian began calling him “Cheap Grace,” a name first coined by

Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

“Cheap grace,” Bonhoeffer said, “means the justification

of sin without justification of the sinner. . . [it is] grace without

discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without Jesus Christ, living and

incarnate” (Cost of Discipleship, 43, 45). Cheap Grace plans to have heaven

without holiness, the salvation without sanctification, forgiveness of sin

without forsaking of sin. He speaks of justification ‘by grace alone’ as a

deer’s head mounts motionless upon the wall. It is but the carcass of orthodoxy.

Reformed Christian understood the grace of justification

always brings the Holy Spirit and transformation. The same grace that redeems

us, also “trains us to say ‘no’ to ungodliness and worldly passions, and to live

self-controlled, upright and godly lives in the present age” (Titus 2:12). The

grace that justifies — manifest in and inseparable from the Person of God’s

grace, Jesus Christ — also sanctifies us. It is grace to be acquitted and

reckoned as holy, and grace also to grow in holiness.

To Luther, as the other Reformers, justifying grace was

costly grace.

It was grace, for it was like water on parched ground,

comfort in tribulation, freedom from the bondage of a self-chosen way, and

forgiveness of all [Luther’s] sins. And it was costly, for, so far from

dispensing him from good works, it meant that he must take the call to

discipleship more seriously than ever before. It was grace because it cost so

much, and it cost so much because it was grace. That was the secret of the

gospel of the Reformation — the justification of the sinner. (Cost of

Discipleship, 49)

Costly grace, Reformed Christian insisted to Cheap

Grace, is “costly because it calls us to follow, and it is grace because it

calls us to follow Jesus Christ. It is costly because it costs a man his life,

and it is grace because it gives a man the only true life. It is costly because

it condemns sin, and grace because it justifies the sinner” (Ibid., 45).

Amazing Grace

Threats to God’s grace in justifying sinners arrive from

two fronts.

On the Roman side, we have a new Galatian heresy; the

unmaking of grace through accompanied meritorious good works. But the

masterpiece of Golgotha has as its caption: Do Not Touch. “For by a single

offering he has perfected for all time those who are being sanctified” (Hebrews

10:14). Ours it is only to receive the blood-painted frame as it is — by grace

alone, as a gift.

On the other side, Cheap Grace brings us to the broken

elevator of presumption. “This mighty lifter named Grace,” we are told, “is

mighty enough to bring us to heaven.” Yet, it is not strong enough to lift us

one floor above the world, the flesh, and the devil. James calls the contraption

The Grace and Faith of Demons. It might borrow language of alien righteousness,

but it applies it as cheap perfume to mask a still rotting corpse.

The Reformers knew the grace of God in justification to

be costly, purchased by Christ on the cross, and arriving as first a justifying

proclamation, and then consequently as a transforming power, through the Spirit,

in sanctification.

For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this

is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works, so that no

one may boast. For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good

works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them. (Ephesians

2:8–10)

The grace of justification — received by the instrument

of faith alone — never remains alone in the person justified. This grace of our

Lord Jesus Christ acquits us in heaven’s court, and trains us to live holy lives

on earth. Grace loves living for Jesus — for Jesus is the perfect manifestation

of the grace of God. This gospel grace of God — the kind that washes over us

divine commendation and divine life — as opposed to its perversions, is worthy

of the name, “Amazing.”

Greg Morse is a staff writer for desiringGod.org and

graduate of Bethlehem College & Seminary. He and his wife, Abigail, live in St.

Paul with their son and two daughters.

Source: desiringGod.org

You are welcome to print and distribute our

resources, in their entirety or in unaltered excerpts, as long as you do not

charge a fee.

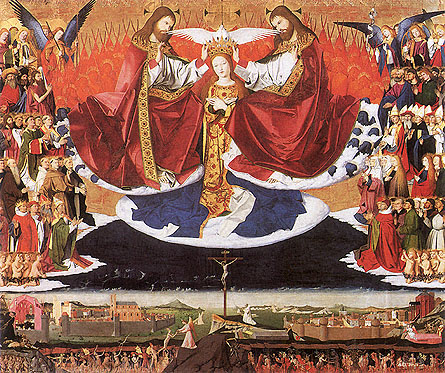

Do you see anything terribly wrong with this picture? I do. This is the Catholic Mary. Look at her hands. Do you see the scars of crucifixion? Did Mary die on the cross for you? No! This photo to the left is blasphemous and creepy! Does this bother you? It should. Look at the caption. It says, Mary, Co-Redemptrix (or co-redeemer). Look again... it says she our "advocate"--but wait a minute. 1st John 2:1 says that Jesus is our advocate with the Father.

"...if any man sin, we have an advocate with the Father, Jesus Christ the righteous."

The Roman Catholic Mary is an IMPOSTER!

Look again, this abominable image also says that Mary "mediates" the grace of God. This is untrue when compared with the Bible. Why is light emitting from her wounds? Is she supposed to be the light of the world and power of God? Wait a minute, notice that she is pregnant. Jesus is supposedly still in her womb, a fetus totally dependent on her. Meanwhile she's all powerful! You may want to see my article "Catholics believe Jesus is a Mama's Boy".

Did you know that Roman Catholics call Mary the "Queen of Heaven"? Did you know that the Bible talks about the queen of heaven? It does. The Queen of Heaven is A PAGAN BABYLONIAN GODDESS, A DEVIL-- Jeremiah 7:18, "The children gather wood, and the fathers kindle the fire, and the women knead their dough, to make cakes to the QUEEN OF HEAVEN, and to pour out drink offerings unto other gods, that they may provoke me to anger."

You can also read about this devil, the Queen of Heaven, in Jeremiah chapter 44. In this little treatise you will see FROM CATHOLIC SOURCES that

From: https://jesus-is-savior.com/

What is the pope doing in this picture? He is not eating lunch, he is praying to a statue/graven image. This picture was found on the Vatican website. Its caption stated, "Fatima, 12 May 2000: John Paul II praying to Our Lady of Fatima". Catholics add iniquity to iniquity by lying about praying to Mary. They sin by praying to her and then sin again by lying and saying that they don't. The pope prays to Mary and so do Catholics. One of the conditions for obtaining the unbiblical jubilee indulgence is PRAYER TO MARY--

CONDITIONS FOR GAINING THE JUBILEE INDULGENCE: 3) In other ecclesiastical territories, if they make a sacred pilgrimage to the Cathedral Church or to other Churches or places designated by the Ordinary, and there assist devoutly at a liturgical celebration or other pious exercise, such as those mentioned above for the City of Rome; in addition, if they visit, in a group or individually, the Cathedral Church or a Shrine designated by the Ordinary, and there spend some time in pious meditation, ending with the "Our Father", the profession of faith in any approved form, and prayer to the Blessed Virgin Mary.

*The page where this information was found was entitled, "Incarnationis Mysterium, BULL OF INDICTION, OF THE GREAT JUBILEE OF THE YEAR 2000." The page begins with a Bull from the pope and is followed by CONDITIONS FOR GAINING THE JUBILEE INDULGENCE. This signature reads, "Given in Rome, at the Apostolic Penitentiary, on 29 November 1998, the First Sunday of Advent. William Wakefield Card. Baum, Major Penitentiary; Luigi De Magistris, Regent."

Another example: the pope was apparently Time Magazine's Man of the Year in 1994. This is a line from the article "On the top right of the first page he inscribes Tuus Totus (All Thine), the opening words of A SHORT PRAYER TO THE VIRGIN..."

It is well known that Karol's (the pope's real name) motto is "Tuus Totus" which signifies his devotion to Mary. "I'm all yours, Mary!", "I'm totally yours, Mary!" That is of the DEVIL! He apparently has a "Tuus Totus" mailing list. Just look up this phrase on the internet and see the truth for yourself. Romanism is warmed over goddess worship. They just call Diana and Astoreth, "Mary". What they do is not Bible but it is pagan.

The

Coronation of Mary Queen of Heaven

The

Coronation of Mary Queen of Heaven

The feast of the Queenship of Mary was established in 1954 by Pope Pius XII. The original date for this feast was chosen as May 31st, but was later moved to the octave day of the feast of the Assumption, August 22nd. This memorial celebrates the same event that is highlighted by the fifth glorious mystery or the Rosary.

Throughout the New Testament, Mary's role in heaven is mentioned. Mary is alluded to as Queen in the book of Revelations [tracy's note: that passage refers to ISRAEL NOT MARY], and throughout the Bible. It is because of Jesus close relationship with his mother that she shares in his kingship.

The Church and the faithful for have also referred to Mary as queen since the fourth century. Various songs, litanies, and prayers refer to Mary as queen. (e.g. Regina Caeli during Eastertide.) The Church has affirmed the title of Mary in modern times through documents including Lumen Gentium (..."and exalted by the Lord as Queen over all things, that she might be the more fully conformed to her Son" Lumen Gentium 59) and the papal encyclical Ad Coeli Reginam.

The title Queen is used to indicate the final state of the Virgin, seated beside her Son, the King of glory.

Queen of Heaven rejoice,

alleluia

The Son whom you merited to bear alleluia

Has risen as he said alleluia

Pray for us to God alleluia

Rejoice and be glad, O Virgin Mary, alleluia!

For the Lord has truly risen alleluia

From: https://jesus-is-savior.com/

What Catholicism Teaches About the Supper

Article by Reid Karr

Guest Contributor

Here in Rome, Italy, near the heart of Roman Catholicism,

it is not unusual to pass by one of the city’s countless Catholic churches and

see people prostrate on the floor or on bended knee as the priest carries around

the bread of the Eucharist.

This is a pinnacle moment in the life of Catholics. They

claim to be worshiping the actual body and actual blood of Christ, which have

taken over the elements of the bread. As The Catechism of the Catholic Church

(CCC) reads,

In the liturgy of the Mass we express our faith in the real

presence of Christ under the species of bread and wine by . . . genuflecting or

bowing deeply as a sign of adoration of the Lord. The Catholic Church has always

offered and still offers to the sacrament of the Eucharist the cult of

adoration. (CCC, 1378)

In the Eucharist, they believe, Christ’s sacrificial work

on the cross is made present, perpetuated, and reenacted. This understanding of

the Eucharist depends on the Catholic Church’s teaching of transubstantiation,

which has a central place in the Catholic faith.

What Is Transubstantiation?

The Catholic Church teaches that during the Eucharist, the

body of Jesus Christ himself is truly eaten and his blood truly drunk. The bread

becomes his actual body, and the wine his actual blood. The process of this

change is called transubstantiation:

By the consecration of the bread and wine there takes place

a change of the whole substance of the bread into the substance of the body of

Christ our Lord and of the whole substance of the wine into the substance of his

blood. This change the holy Catholic Church has fittingly and properly called

transubstantiation. (CCC, 1376)

To explain this phenomenon, Catholic theology presses

Aristotelian philosophy into service. A distinction is made between substance

and accidents. The substance of a thing is what that thing actually is, while

accidents refer to incidental features that may have a certain appearance but

can be withdrawn without altering the substance.

During the Eucharist, then, the substance of the bread and

wine are changed into the body and blood of Christ, while the accidents remain

the same. The bread and wine actually become the body and blood of Christ, it is

claimed, but maintain the appearance, texture, smell, and taste of bread and

wine. The Catholic Church does not claim that this is a magical transformation,

but that it is instead a sacramental mystery that is administered by those who

have received the sacrament of order.

Where Did Transubstantiation Come From?

Like many aspects of Roman Catholic theology and practice,

it is difficult to point to one definitive person or event to explain how

transubstantiation entered into Catholic Church. It was more of a gradual

development that then reached a decisive moment at the Fourth Lateran Council in

1215, where the teaching and belief were officially affirmed. However, by the

second century, the view that the bread and wine are in some unspecified way the

actual body and blood of Jesus had already surfaced. This is evidenced, for

example, in the writings of Ignatius of Antioch (died around AD 108) and Justin

Martyr (died AD 165), though their references to the nature of the Eucharist are

somewhat ambiguous.

It is also true, however, that the early church fathers

were countering certain gnostic teachings that claimed that Jesus never had a

real human body but was only divine in nature. It was not possible, said the

critics, that his body was present during the Eucharist. In response, some early

church fathers insisted on the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the

sacrament. Moreover, both Origen (185–254) and Cyprian (200–258) spoke of the

sacrament as a eucharistic sacrifice, thus unhelpfully introducing sacrificial

language into the Lord’s Supper. Ambrose of Milan (died 397) understood the

Eucharist in these sacrificial terms, as did John Chrysostom (died 407). Jesus’s

words in John 6:53–56 appeared to provide the biblical framework they needed to

make their argument: “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of

the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you” (John 6:53).

Over the centuries, this belief developed until it

eventually became official church dogma. It would not be without its

challengers, however. Ratramnus (ninth century) and Berengarius (eleventh

century) are notable examples of those who did not accept the claim that the

substance of the bread and wine change in the Supper.

“To say that transubstantiation teaches that God is eaten

is not an exaggeration or a misrepresentation.”

Transubstantiation would receive its greatest challenge in

the sixteenth century from the Protestant Reformation. During the Council of

Trent (1545–1563), which was the Catholic response to the Protestant

Reformation, the Roman Catholic Church renewed with great enthusiasm its

commitment to the doctrine, and thus to the conviction that during the

Eucharist, God incarnate is indeed eaten. Matteo Al-Kalak — a professor of

modern history at the University of Modena-Reggio in Italy — affirms that this

concept is still fully embraced in a recent book titled Mangiare Dio: Una storia

dell’eucarestia — Eating God: A History of the Eucharist. To say that

transubstantiation teaches that God is eaten is not, then, an exaggeration or a

misrepresentation.

His Sacrifice Cannot Be Repeated

The Protestant Reformation rightly rejected the Roman

Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation. In the Old Testament, the priests

entered the tabernacle repeatedly in order to offer blood sacrifices for the

sins of God’s people. Christ, however, by means of his death and resurrection,

entered into heaven and mediates on our behalf once and for all (Hebrews 7:27).

His is not a sacrifice that needs to be or even can be repeated (Hebrews

9:11–28). It is sufficient. It is final (John 19:30). If, however, the bread and

wine of the Eucharist indeed undergo a change of substance and become the real

body and blood of Christ, Christ’s sacrifice on the cross is neither sufficient

nor final; instead, it is continually re-presented and made present. Thus,

transubstantiation undermines the clear teachings of Scripture.

“Christ’s is not a sacrifice that needs to be or even can

be repeated. It is sufficient. It is final.”

In response, Martin Luther (1483–1546) proposed a somewhat

confused alternative with his doctrine of what came to be called

consubstantiation. He taught that Christ’s body and blood are substantially

present alongside the bread and wine. This was different from transubstantiation

in that there was no change in the substance of the bread and wine itself.

Luther’s theory, however, was susceptible to similar objections to those of

transubstantiation. Huldrych Zwingli (1484–1531), another Reformer and

contemporary of Luther, promoted the idea that the Lord’s Supper is symbolic and

is solely a memorial of Christ’s work on the cross. Zwingli’s view is widely

accepted in many evangelical circles today.

Transubstantiation receives its most helpful answer and

alternative, however, in the classic Reformed view of the Lord’s Supper,

deriving from John Calvin (1509–1564). The Reformed view promotes the

understanding that while there is no change of substance in the sacrament, Jesus

Christ is nonetheless present in a real way by means of his Holy Spirit. In

observing the Lord’s Supper, Christ does not come down to the faithful in his

body and blood; instead, the faithful are lifted up to him in spirit by the Holy

Spirit.

As truly as the faithful eat in faith the bread and drink

the wine, so they spiritually feed on Christ. The physical and spiritual are not

merged, as they are in transubstantiation, nor are they completely separated.

Instead, they are distinct but at the same time, through the ministry of the

Spirit and the exercise of genuine faith, inseparable.

Reid Karr is a church planter in Rome, Italy, and co-leads

the evangelical church Breccia di Roma San Paolo. He is also the Associate

Director of the Reformanda Initiative, and co-hosts the Reformanda Initiative

podcast that discusses Roman Catholic theology and practice from an evangelical

perspective.

Source: desiringGod.org

You are welcome to print and distribute our resources, in their entirety

or in unaltered excerpts, as long as you do not charge a fee.

A Reformed Perspective and Response

Article by Robert Letham

Professor, Wales Evangelical School of Theology

Orthodoxy comprises a range of autonomous churches, the

Russian and Greek being the most prominent. During the first millennium of the

church, the Latin West and the predominantly Greek-speaking East drifted apart

linguistically, culturally, and theologically. Rome’s claims to universal

jurisdiction and its acceptance of the filioque clause led to severed relations

in 1054. Many countries in the East, overrun by the Muslims, had limited

freedom. Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453, while in the twentieth

century, Orthodoxy in Russia and Eastern Europe endured under Communist rule,

suffering intense persecution.

Orthodoxy is emphatically not to be identified with Rome.

Ecclesiastically, it has no unified hierarchy, no pope, no magisterium. It lacks

the barrage of dogmas of the Roman Church. Its doctrinal basis, such as it is,

is the seven ecumenical councils, referring principally to the Trinity and

Christology, the vast majority of which Protestants embrace. While at the

popular level some Marian dogmas are accepted, they are not accorded official

status. Nor is there a requirement for converts from Protestantism to renounce

justification by faith alone. Particularly distinctive is its dominantly visual

worship; icons fill its churches. Its ancient liturgy, rooted in the fourth

century, is central to its theology and life.

If Orthodoxy differs so significantly from Catholicism, how

closely does it resemble Protestantism? A brief overview of Orthodoxy reveals

several points of alignment, some significant misunderstandings, and a few major

disagreements with Protestantism.

Learning from Orthodoxy

First, Protestants can learn from many positive elements in

Orthodoxy.

The Orthodox liturgy, for starters, is full of Trinitarian

prayers, hymns, and doxologies. The Trinity is a vital part of their belief and

worship. This finds biblical precedent as Paul describes our relationship with

God in Trinitarian terms: “Through [Christ] we . . . have access by one Spirit

to the Father” (Ephesians 2:18).

Another positive element in Orthodoxy is their teaching on

union with Christ and God. Crucial to Orthodox theology is deification, in which

humans are indwelt by the Holy Spirit and transformed by divine grace. Orthodox

theology has maintained a focus on the union of the three persons in God, the

union of deity and humanity in Christ, the union of Christ and the church, and

the union of the Holy Spirit and the saints. In some forms, Orthodoxy’s focus on

deification enters the realm of mysticism. But in other strands, exemplified by

the Alexandrians, Athanasius (295–373), and Cyril (378–444), it is the

equivalent of regeneration, adoption, sanctification, and glorification viewed

as one seamless process.

In addition, unlike the Western church, the Orthodox Church

has enjoyed freedom from concerns raised by the Enlightenment. Due to its

historical and cultural isolation, Orthodoxy has experienced no Middle Ages, no

Renaissance, no Reformation, and no Enlightenment. Until recently, it was not

preoccupied with critical attacks of unbelief, which in the West have sometimes

bred a detached, academic approach to theology divorced from the life of the

church. This is evident in Orthodoxy’s firm belief in the return of Christ and

heaven and hell, topics often sidelined in the West due to possible

embarrassment.

Finally, the Orthodox Church keeps together theology and

piety. Asceticism and monasticism have had a contemplative character. The

knowledge of God is received and cultivated in prayer and meditation in battle

against the forces of darkness. Since the Enlightenment, Western theology has

centered in academic institutions unconnected to the church. Orthodoxy has

profoundly integrated liturgy, piety, and doctrine.

Points of Alignment

Beyond these positive elements in Orthodoxy from which

Protestants can learn, there are many areas of agreement between Protestantism

and Orthodoxy.

The ecumenical councils’ declarations on the Trinity and

Christ show the extensive agreement between Orthodoxy and classic Protestantism,

despite disagreement on the filioque.

With different emphases, the Orthodox and evangelical

Protestants agree on the authority of the Bible, sin and the fall (although the

Orthodox do not accept the Augustinian doctrine of original sin), Christ’s death

and resurrection (although the atonement is regarded more as conquest of death

than as payment for the penalty of the broken law), the Holy Spirit, the return

of Christ, the final judgment, and heaven and hell.

Although the Reformation controversies passed the East by,

occasionally Orthodox fathers talk of salvation and of faith as gifts of God’s

grace, while the Orthodox liturgy repeatedly calls on the Lord for mercy to us

as sinners, as does the famous Jesus prayer. At root, justification has not been

an issue and so has not provoked discussion. Similarly, there are echoes in the

West of deification — in Augustine, Aquinas, Calvin, and some Puritans — for,

understood in the way Athanasius and Cyril did, deification is no more

incompatible with justification by faith than are sanctification and

glorification.

Additionally, the Orthodox doctrine of the church stresses

its unity, the parity of bishops and of all church members, underlying its

opposition to Rome. This is a model close to Anglicanism.

Significant Misunderstandings

Historically, however, Protestant and Orthodox believers

have often misunderstood one another.

To start, Protestants tend to misunderstand the Eastern

understanding of icons. Nicea II (AD 787) emphatically denied that icons are

worshiped. Following John of Damascus (675–749), the council distinguished

between honor (proskunēsis) given to saints and icons, and worship (latreia)

owed to the indivisible Trinity alone. Icons are seen as windows to the

spiritual realm, indicating the presence in the church’s worship on earth of the

saints in heaven. Moreover, the idea of image (eikon) is prominent in the Bible.

The whole creation reveals the glory of God (Psalm 19:1–6; Romans 1:18–20).

Reformed theology, in general revelation, views the whole world as an icon.

No problem exists with intercession among saints as such,

for we all pray for and with living saints; we have prayer meetings. However,

the Bible does not encourage us to pray to departed saints, for there are no

grounds to suppose that they hear us. Rather, Scripture directs our hope to

Christ, his return, and the resurrection (1 Thessalonians 4:13–18).

On Scripture and tradition (the teaching of the church),

both sides appeal to both sources. There is an overwhelming biblical emphasis in

Orthodox liturgy, while the Reformation had a high view of the teaching of the

church. The issue is not the Bible versus tradition, but rather which has the

decisive voice. For evangelicalism, the Bible is unequivocally the word of God

(2 Timothy 3:16), while all human councils may err.

From the Orthodox side, many confuse the Protestant

doctrine of predestination with Islamic fatalism. The Bible teaches both the

absolute sovereignty of God and the full responsibility of man, God’s decrees

not undermining the free actions of secondary causes. As such, the Orthodox idea

that the doctrine of predestination short-circuits the human will, and is

effectively monothelite, is misplaced.

Many Orthodox polemicists also accuse evangelicals of

ignoring the church’s part in Scripture. However, the classic Protestant

confessions attest that the church is integral to the process of salvation, the

Christian faith being found in the Bible and taught by the church. Both

Scripture and the church are originated by the Holy Spirit. Church and covenant

are integral to Reformed theology. Orthodoxy often confuses classic

Protestantism with today’s freewheeling individualists.

Major Disagreements

Beyond these points of alignment and misunderstanding,

significant differences do exist.

First, the East tends to downplay preaching. Largely due to

the impact of Islam, and despite Orthodoxy’s heritage of superlative preaching

(Chrysostom and Gregory Nazianzen, among others), their liturgy is more visual.

Sermons are part of the liturgy, but the focus is more on the icons and the

symbolic movements of the clergy.

Next, the relationship between Scripture and tradition

differs. For Orthodoxy, tradition is a living dynamic movement — the Bible

existing within it, not apart from it. This was the position of the church of

the first two centuries, with the Bible and tradition effectively

indistinguishable. Later developments in the West placed tradition over

Scripture (medieval Rome), or pitted Scripture against tradition (the

anabaptists, some evangelicals), or put Scripture over tradition without

rejecting it (the Reformation, the Reformed churches). For Orthodoxy, Scripture

is not the supreme authority.

A third distinction is found in what’s called the Palamite

doctrine of the Trinity. Gregory Palamas’s distinction between the unknowable

essence (being) of God and his energies has driven a wedge between God in

himself and God as he has revealed himself, threatening our knowledge of God

with profound agnosticism. It introduces into God a division, not a distinction.

The Christian life easily becomes mystical contemplation.

Along with Rome, the East venerates Mary and the saints.

Orthodoxy considers it possible, legitimate, and desirable to pray to departed

saints. But there is no biblical evidence that this is possible.

Finally and most crucially, Orthodoxy has what we might

call soteriological synergism. The East has a vigorous doctrine of free will and

an implacable opposition to the Protestant teaching on predestination and the

sovereignty of God’s grace in salvation. This puts Orthodoxy further away from

the Reformation than is Rome.

How Far Away Is the East?

Compared with Rome, how far away from Protestantism is

Orthodoxy?

Orthodoxy is closer to classic Protestantism than is Rome

in a number of ways. Both were forced into separation, and both oppose the

claims of the papacy. The structure of the Orthodox churches is closer to

Anglicanism than Catholicism. Orthodoxy does not have the same accumulation of

authoritative dogmas as Rome. Its stress on the Bible opens up a large

commonality of approach.

In other ways, Orthodoxy is further removed from

Protestantism than is Rome. Protestantism, with Rome, is part of the Latin

church, shares the same history, and addresses the same questions. Its faith is

centered in Christ; the East’s is more focused on the Holy Spirit, along with a

more mystical theology and practice. As Kallistos Ware puts it, Rome and

Protestantism share the same questions, but supply different answers; with

Orthodoxy the questions are different.

Robert Letham is a lecturer in systematic and historical

theology at Wales Evangelical School of Theology and author of Systematic

Theology.

Further Info on Apologetics

https://www.britannica.com/topic/apologetics

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apologetics

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/apologetic

https://bible.org/seriespage/1-what-apologetics

https://www.crossway.org/articles/10-things-you-should-know-about-apologetics/