Saint

Ephraim the Syrian Prose Refutations

(Ephraem Syrus)

St. Ephraim's Prose Refutations of Mani, Marcion and Bardaisan.

Transcribed from the Palimpsest B.M. Add. 14623 by the late C. W. MITCHELL,

M.A., C.F.

·

Introduction to volume

1 (1912)

·

Discourse to Hypatius I

·

Discourse to Hypatius II

·

Discourse to Hypatius III

·

Discourse to Hypatius IV

·

Discourse to Hypatius V

·

Introduction to volume 2 (1921)

·

Against Bardaisan's "Domnus"

·

Against Marcion I

·

Against Marcion II

·

Against Marcion III

·

Stanzas Against Bardaisan

·

On Virginity

·

Against Mani

·

Introduction by F.C.Burkitt.

S.

Ephraim's Prose Refutations of Mani, Marcion and Bardaisan. Transcribed from the

Palimpsest B.M. Add. 14623 by C. W. MITCHELL, M.A., volume 1 (1912).

Introduction

S. EPHRAIM'S PROSE REFUTATIONS

OF

MANI, MARCION, AND BARDAISAN

OF WHICH

THE GREATER PART HAS BEEN TRANSCRIBED FROM THE PALIMPSEST B.M. ADD. 14623 AND IS

NOW FIRST PUBLISHED

BY

C. W.

MITCHELL, M.A.

FORMERLY RESEARCH STUDENT EMMANUEL

COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE

VOLUME I

THE

DISCOURSES ADDRESSED TO HYPATIUS

PUBLISHED FOR, THE TEXT AND

TRANSLATION SOCIETY

BY

WILLIAMS AND NORGATE

14, HENRIETTA STEEET, COVENT

GARDEN, LONDON,

AND 7, BROAD STREET, OXFORD

1912

LONDON :

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED,

DUKE STREET, STAMFORD STREET, S.E., AND GREAT WINDMILL STREET, W.

PREFACE

THE work of which this volume contains the first

two parts was begun when I held a Research Studentship at Emmanuel College,

Cambridge. It was then my intention to publish a translation of the fragments of

S. Ephraim's prose refutation of the False Teachers, published by Overbeck ("S.

Ephraemi Syri aliorumque opera selecta," pp. 21-73), and considered to be a

valuable document for the history of early Manichaean teaching. In undertaking

this I could not foresee that the work would extend over such a long period, or

that it would, when complete, pass so far beyond the limits of my original plan.

An unexpected enlargement of it has been made possible and has developed in the

following way.

Before I had finished the translation of the

Overbeck section, Professor Bevan, who had suggested the work, informed me that

the remainder of Ephraim's Refutation was extant in the palimpsest B.M. Add.

14623. Wright's description of this manuscript did not encourage the hope that

the underwriting could be deciphered. On p. 766 of the catalogue of Syriac

Manuscripts he referred to it thus: "As stated above, the volume is palimpsest

throughout, and the miserable monk Aaron deserves the execration of every

theologian and Syriac scholar for having destroyed a manuscript of the sixth

century written in three columns containing works of Ephraim . . ." These words

not only state with emphasis Wright's opinion of the importance of the

manuscript, but also suggest, I think, his fear that its original contents were

lost. While I add, in passing, that they may also be taken to indicate the

satisfaction which the recovery of that text would have brought him—a text of

which he knew the first part intimately through his active share in the

preparation of Overbeck's volume—, I may also venture to express here, by

anticipation, the hope that, after the whole of the present work has been

published, both Theology and Scholarship may consent to modify the severity of

this verdict on ill-fated Aaron.

On examining this palimpsest of eighty-eight

leaves, I found that the older writing on a few pages could be read with ease,

on a good number of others with much difficulty; while in

|2 each of

these legible pieces there were more or less irrecoverable passages, and worst

of all, only one side of the leaves could be read, except in two or three

cases, though there was evidence that the writing was lurking in obscurity

below.

I decided to edit as many of the pages as were

fairly legible, and to publish them along with the translation which I have

mentioned above. After I had worked at the palimpsest for a considerable time,

my gleanings amounted to over thirty of its pages. But the illegibility of one

side of the vellum, coupled with the confusion arising from the disturbance of

the original order of the leaves and quires in the hands of the monk Aaron, made

it impossible to arrange the deciphered pages so that they could be read

consecutively. As they had been transcribed with tolerable completeness, most of

them containing about a hundred manuscript lines, and as each page was a section

from a genuine work of Ephraim against Mani, Marcion, and Bardaisan, the Text

and Translation Society undertook the expense of publishing them as isolated

Fragments.

In 1908 the pages, grouped in the best way

possible according to their subject-matter, began to be printed. Nearly one half

of them had passed through the press when the work was unexpectedly stopped by a

most fortunate turn of events. Dr. Barnett, Keeper of Oriental Manuscripts at

the British Museum, began to apply a re-agent to the illegible portions of the

palimpsest, and so wonderfully did its virtue revive the energies of the ancient

ink, so distinctly did the underwriting show itself, here readily, there

reluctantly, that it now became possible to transcribe almost the entire

contents. In consequence, too, of his action, I was able to reconstruct the

order of the leaves and quires, and to assign the former Fragments to their

proper places in the original document.

It will thus not be difficult to see how these

successive extensions of my first project prevented the appearance of the volume

at the times promised. I feel, however, that the work has, in the meantime,

gained so much in character and importance, that the facts which I have stated

above will be a sufficient explanation to the members of the Text and

Translation Society for what may have seemed vexatious delays. Instead of a text

and translation of a collection of fragments, torn from their context, and

suffering greatly from illegible gaps, this volume and that which is to follow

it are now able to present to "the theologian and Syriac scholar" the text and

translation of Ephraim's "Contra Haereses" approximately complete. The lacunae

which still remain will not, I think, be found to affect seriously the

elucidation of many passages of importance.

Even with the help of the re-agent, the work of

transcribing

|3 the

palimpsest has been necessarily slow. Not to speak of the arduousness of the

decipherer's task, which anyone who has had experience of such work will

appreciate, there have been in the present case unusual difficulties owing to

the fact that no other copy of the underwriting is extant. Such difficulties are

inevitable when the decipherer's aim is not collation, but the recovery of a

lost document. In a field of this kind pioneer work cannot go on rapidly ; for

it constantly happens that advance is only possible by verifying and re-verify

ing one's conjectures as to probable words and letters in passages which at

first sight seem all but obliterated.

The time, moreover, which I have been able to

devote to the work has been limited by my other duties, and has often been

rendered still more scanty by the weather. Accurate deciphering is only possible

under a good sunlight, and London has never claimed an abundance of this among

her varied endowments. When bright days have been absent, in the interests of

completeness and accuracy I have been obliged to postpone both transcribing and

proof-correcting. For, however much the editor of such a work as the present may

hope, for the sake of mistakes which he may have allowed to creep in, that he

may not be transcribing e's act, yet he must feel that, as the writing soon

fades back to that underworld from which it has recently emerged only after a

thousand unbroken years of obscurity, there is laid upon him a special

responsibility to attain finality in transcription. At the same time, he is

aware that there comes a temptation to linger too frequently and painfully over

sparse after-gleanings. Perhaps I have sometimes erred in this respect, but at

any rate I feel that this edition presents a maximum of text recoverable from

the palimpsest, and I have no hope that the lacunae can be filled by a more

prolonged study of it.

I have tried to make a literal translation, and

for the sake of clearness have introduced marginal summaries. The difficulty of

the Syriac of the published fragment of the second Discourse was formerly noted

by Nöldeke (ZDMG for 1889, p. 543), and the remainder of the work is

written in the same style.

In the next volume containing Parts III. and

IV.—the latter of which is now being printed—there will appear the text and

translation of an unedited work of Ephraim, called "Of Domnus." It consists of

Discourses against Mani, Marcion, and Bardaisan, and a Hymn on Virginity. The

Discourses against Bardaisan are remarkable as showing the influence of the

Platonists and the Stoics around Edessa.

In the third volume, Part V., I shall endeavour to

collect, arrange, and interpret the evidence derived from the first two volumes

for the teaching of Mani, Marcion, and Bardaisan. In that

|4 connection

notes will be found on special points, e.g., the references to the Hymn

of the Soul, Vol. i, pp. lxxxix., cv.-cvii.; BÂN the Builder, p. xxx.; BOLOS, p.

lxxii.; HULE, p. xcix. f.; Mani's Painting, p. xcii.; the Gospel quotations,

e.g. pp. xc., c. Part V. will also contain indices for the whole work.

Throughout the first volume Ephraim directs his

main attack against the teaching of Manichaeism—'perhaps the most formidable

rival that the Church has encountered in the whole course of her history.' If

that system ultimately failed on the favourable soil of Syria, its defeat must

have been in some measure hastened by the weapons forged by Ephraim, and stored

up in these Discourses to Hypatius, to be used by others in proving that

Manichaeism could not justify itself intellectually to the Syrian mind.

I could wish to make my recognition of Professor

Bevan's help as ample as possible. In editing the text, in conjectural

emendations, and, above all, in the translation, I have had his constant and

generous assistance. Throughout the work I have received from him encouragement

and help of the most practical kind. For its final form, of course I alone am

responsible.

I desire to express my thanks to Dr. Barnett, who

has taken the greatest pains to restore the Manuscript to legibility, and who by

his courtesy and kindness has greatly facilitated my progress with this work. I

am also deeply grateful to Dr. Burkitt, who has given me advice and many

suggestions ; and to my colleagues the Rev. F. Conway and Mr. C. E. Wade for

help on certain points.

To the Text and Translation Society, who undertook

the publication of the work, and to the Managers of the Hort Fund for two grants

in connection with it, I beg here to offer my sincere thanks.

C. W.

MITCHELL.

MERCHANT TAYLORS' SCHOOL,

LONDON.

CONTENTS

|

PAGE

|

|

INTRODUCTORY NOTES

|

(3)-(10)

|

|

TRANSLATION OF THE FIVE DISCOURSES

|

i-cxix

|

|

SYRIAC

TEXT OF DISCOURSES II-V

|

1-185

|

|

|

|

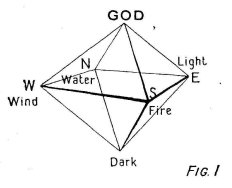

PLATE I

|

To

face Title-page

|

|

PLATE

II

|

To face

p.

(4)

|

MANUSCRIPTS OF THE FIVE DISCOURSES ADDRESSED TO HYPATIUS.

Two manuscripts—B.M. Add. 14570 and B.M. Add.

14574— have preserved the First Discourse. The first of these is fully described

in Wright's Catalogue of Syriac Manuscripts, pp. 406-7. This small volume

contains as well a Discourse of Ephraim "On our Lord." It is written in a small

elegant Estrangela of the fifth or sixth century, and each page is

divided into two columns. On the first page there is a note stating that this

was one of the two hundred and fifty volumes brought to the convent of S. Mary

Deipara by the Abbot Moses of Nisibis, A.D. 932.

As regards the other manuscript, only the part of

it numbered DXXXV by Wright, and described on pp. 407-8, requires mention here.

Its nineteen leaves are "written in a fine regular Estrangela of the VIth

century," each page being divided into three columns with from 34 to 38 lines to

each. They contain not only the First Discourse but a fragment of the Second, (Overbeck,

pp. 59-73) and originally belonged to the palimpsest Add. 14623, of which

they formed the first nineteen leaves. Along with the eighty-eight leaves of

this palimpsest, to which reference has already been made in the Preface, they

formed a volume containing "To Hypatius" and "Of Domnus," two works which

Ephraim intended to be his great refutation of the False Teachings. It thus

becomes evident that the text of Discourses II-V, edited in Part ii., pp. 1-185,

is really derived from a single manuscript, although, according to the

Catalogue, the nineteen leaves and the palimpsest portion appear under different

numbers.

When this sixth-century volume was rendered a

palimpsest by

|3 the monk

Aaron, c. A.D. 823, fortunately the above-mentioned fragments—its first nineteen

leaves—'escaped his ruthless hands.' But the surface of the remaining

eighty-eight leaves suffered a ruinous transformation through his zealous

attempt to remove the writing, and the treated vellum was re-arranged into new

quires. The long list of works which the renovated codex was destined to contain

can be seen on pages 464-7 of the Catalogue.

The two plates, one facing the title-page, the

other opposite this page, show the present appearance of the manuscript. They

have been reproduced from photographs of both sides of folio 13, which is a fair

specimen of the leaves. It will.be noticed that the underwriting on the first

plate is fairly clear, while that on the second plate showing the other side of

the same leaf is, except for the title, completely illegible. The text of both

has been transcribed with the help of the re-agent. The photographs have lost

somewhat in distinctness in the process of reproduction.

On folio 88b there are two notes of

interest in connection with the history of this palimpsest (CSM, p. 766).

From the first we learn that Aaron was a Mesopotamian monk, a native of Dara,

and that he wrote his manuscript in the Thebaid of Egypt. His date given above

shows that Add. 14623 is one of the earliest palimpsests in the Nitrian

Collection. Another note on the same page states that the volume was presented

with nine others to the convent of S. Mary Deipara, by Isaac, Daniel and

Solomon, monks of the Syrian convent of Mar Jonah in the district of

Maris or Mareia. A.D. 851-859.

The manuscript was brought from the Nitrian desert

by Archdeacon Tattam, and has been in the British Museum since March, 1843.

SIZE

AND ARRANGEMENT OF THE WORK.

At the head of the First Discourse in B.M. Add.

14574, the following title is found : "Letters of the Blessed Ephraim, arranged

according to the letters of the alphabet, against the False Teachings." On this

Wright remarked that although the words "arranged according to the letters of

the alphabet" appear to imply that there were originally twenty-two of these

Discourses, following one another like those of Aphraates in the order of the

Syriac alphabet, yet this "seems unlikely as the second Discourse begins with

the letter p" (CSM, p. 408).

The exact meaning of the words remained obscure

till Professor Burkitt, after examining the palimpsest portion of the work,

showed that it consisted of five Discourses arranged acrostically in the order

of the five letters of the author's name. He also observed that "a similar

method of signature is actually used by Ephraim in the Hymn added at the end of

the Hymns on Paradise (Overbeck, p. 351 ff.), the several stanzas of

which begin with the letters

m Y r p ) " (Texts and Studies, vol.

vii-2, pp. 73, 74).

The decipherment of the palimpsest makes it

possible to complete Professor Burkitt's evidence (op. cit. p. 74) thus

:—

|

The

First Discourse begins

|

mYrp) )

|

|

The

Second Discourse begins

|

tY)$wrp

|

|

The

Third Discourse begins

|

Yl)gr r

|

|

The

Fourth Discourse begins

|

xrY Y

|

|

The

Fifth Discourse begins

|

)tOM$M M

|

|5

TABLE I

SHOWING

THE RELATION OF PRIMITIVE QUIRES TO THE MODERN ARRANGEMENT

|

Ancient

|

|

|

|

Modern

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Quire

and Leaf

|

|

|

|

Quire

and Leaf

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I

|

|

Original order preserved in B.M. Add. 14574

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

II

|

|

Original order preserved in B.M. Add. 14574

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

B.M.

Add. 14623

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

III

|

1

|

=

|

Folio

14

|

=

|

II

|

6

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┐

|

|

2

|

=

|

10

|

=

|

|

2

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┐

|

|

|

|

3

|

=

|

9

|

=

|

|

1

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┐

|

|

|

|

|

|

4

|

=

|

12

|

=

|

|

4

|

—

|

—

|

┐

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5

|

=

|

16

|

=

|

|

8

|

—

|

┐

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6

|

=

|

11

|

=

|

|

3

|

—

|

┘

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7

|

=

|

15

|

=

|

|

7

|

—

|

—

|

┘

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8

|

=

|

18

|

=

|

|

10

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┘

|

|

|

|

|

|

9

|

=

|

17

|

=

|

|

9

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┘

|

|

|

|

10

|

=

|

13

|

=

|

|

5

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┘

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IV

|

1

|

=

|

Folio

19

|

=

|

III

|

1

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┐

|

|

2

|

=

|

22

|

=

|

|

4

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┐

|

|

|

|

3

|

=

|

21

|

=

|

|

3

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┐

|

|

|

|

|

|

4

|

=

|

23

|

=

|

|

5

|

—

|

—

|

┐

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5

|

=

|

20

|

=

|

|

2

|

—

|

┐

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6

|

=

|

27

|

=

|

|

9

|

—

|

┘

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7

|

=

|

24

|

=

|

|

6

|

—

|

—

|

┘

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8

|

=

|

26

|

=

|

|

8

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┘

|

|

|

|

|

|

9

|

=

|

25

|

=

|

|

7

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┘

|

|

|

|

10

|

=

|

28

|

=

|

|

10

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┘

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

V

|

1

|

=

|

Folio

29

|

=

|

IV

|

1

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┐

|

|

2

|

=

|

36

|

=

|

IV

|

8

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┐

|

|

|

|

3

|

=

|

44

|

=

|

V

|

6

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┐

|

|

|

|

|

|

4

|

=

|

34

|

=

|

IV

|

6

|

—

|

—

|

┐

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5

|

=

|

46

|

=

|

V

|

8

|

—

|

┐

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6

|

=

|

41

|

=

|

V

|

3

|

—

|

┘

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7

|

=

|

33

|

=

|

IV

|

5

|

—

|

—

|

┘

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8

|

=

|

43

|

=

|

V

|

5

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┘

|

|

|

|

|

|

9

|

=

|

31

|

=

|

IV

|

3

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┘

|

|

|

|

10

|

=

|

38

|

=

|

IV

|

10

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┘

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

VI

|

1

|

=

|

Folio

42

|

=

|

V

|

4

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┐

|

|

2

|

=

|

39

|

=

|

V

|

1

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┐

|

|

|

|

3

|

=

|

35

|

=

|

IV

|

7

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

┐

|

|

|

|

|

|

4

|

=

|

47

|

=

|

V

|

9

|

—

|

—

|

┐

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5

|

=

|

37

|

=

|

IV

|

9

|

—

|

┐

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6

|

=

|

30

|

=

|

IV

|

2

|

—

|

┘

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7

|

=

|

40

|

=

|

V

|

2

|

—

|

—

|

┘

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

rest of the Quire belongs

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

to Vol.

II

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TABLE

II

GIVING

THE TRANSCRIBED LEAVES OF THE PALIMPSEST ACCORDING TO THE ORDER OF THEIR

NUMBERING IN THE CATALOGUE, AND THE PAGES OF THE PRESENT VOLUME ON WHICH THE

TEXT OF EACH LEAF BEGINS

|

Folio 9

|

begins

on page

|

33

|

|

Folio

17

|

begins

on page

|

59

|

|

10

|

"

|

28

|

|

18

|

"

|

55

|

|

11

|

"

|

46

|

|

19

|

"

|

68

|

|

12

|

"

|

37

|

|

20

|

"

|

85

|

|

13

|

"

|

63

|

|

21

|

"

|

77

|

|

14

|

"

|

23

|

|

22

|

"

|

72

|

|

15

|

"

|

50

|

|

23

|

"

|

81

|

|

16

|

"

|

42

|

|

24

|

"

|

94

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Folio

25

|

begins

on page

|

103

|

|

Folio

37

|

begins

on page

|

173

|

|

26

|

"

|

98

|

|

38

|

"

|

151

|

|

27

|

"

|

89

|

|

39

|

"

|

160

|

|

28

|

"

|

107

|

|

40

|

"

|

181

|

|

29

|

"

|

111

|

|

41

|

"

|

133

|

|

30

|

"

|

176

|

|

42

|

"

|

155

|

|

31

|

"

|

146

|

|

43

|

"

|

142

|

|

32

|

belongs

to Vol. II

|

|

|

44

|

"

|

120

|

|

33

|

begins

on page

|

137

|

|

45

|

belongs

to Vol. II

|

|

|

34

|

"

|

124

|

|

46

|

begins

on page

|

129

|

|

35

|

"

|

164

|

|

47

|

"

|

168

|

|

36

|

"

|

115

|

|

|

|

|

PART I.—TRANSLATION

|

THE

FIRST DISCOURSE

|

pp.

i-xxviii

|

|

THE

SECOND DISCOURSE

|

pp.

xxix-l

|

|

THE

THIRD DISCOURSE

|

pp.

li-lxxiii

|

|

THE

FOURTH DISCOURSE

|

pp.

lxxiv-xci

|

|

THE

FIFTH DISCOURSE

|

pp.

xcii-cxix

|

[Short lacunae are indicated in the translation

by dots, and longer gaps by asterisks, but in neither case is the number of the

dots or asterisks intended to bear any exact relation to the number of the

missing words. In respect to this an approximately correct inference may be

drawn by consulting the Syriac text.

Double inverted commas mark quotations where

the original has [Syriac]

Single inverted commas are used in numerous

cases where the words seem to be quotations or to belong to a special

terminology.

Words in italics inside square brackets are to

be regarded as conjectural translations or paraphrases.

In a few passages, where the text has suffered

great mutilation, italics indicate an attempt to summarise the argument from

suggestions in the fragments.]

This text was transcribed by Roger Pearse, Ipswich, UK, September 2002. All material on this page is in the public domain - copy freely.

Greek text is rendered using the Scholars Press SPIonic font, Syriac using the SPEdessa font, both free from here.

A VOLUME OF

SELECTED DISCOURSES

OF THE

BLESSED SAINT EPHRAIM.

THE FIRST AGAINST THE FALSE TEACHERS

EPHRAIM 1 to Hypatius my brother

in our Lord—greeting : may peace with every man increase for us and may the

peace which is between us abound, in the peace of truth may we be established,

and let us make especial use of the greeting (conveyed) in a letter.2

I write a letter though I

would rather have come

to see thee in person. |

Behold, I am writing willingly something that I did not wish to write. For I

did not wish that a letter should pass between us, since it cannot ask or be

asked questions ; but I had wished that there might pass between us a discourse

from mouth to ear, asking and being asked questions. The written document is the

image of the composite body, just as also the free tongue is the likeness of the

free mind. For the body cannot add or subtract anything from the measure of its

stature, nor can a document add to or subtract from the measure of its writing.

But a word-of-mouth discourse can be within the measure or without the measure.

| For great is the gift of Speech. |

For the Deity gave us Speech that is free like Itself, in order that free

Speech might serve our independent Freewill. And by Speech, too, we are the

likeness of the Giver of it, [Ov. p. 22.] inasmuch as by means of it we have

impulse and thought for good things; and not only for good things, but we learn

|ii also of God, the fountain of good

things, by means of Speech (which is) a gift from Him. For by means of this

(faculty) which is like God we are clothed with the likeness of God. For divine

teaching is the seal of minds, by means of which men who learn are sealed that

they may be an image for Him Who knows all. For if by Freewill Adam was the

image of God, it is a most praiseworthy thing when, by true knowledge, and by

true conduct, a man becomes the image of God. For that independence exists in

these also. For animals cannot form in themselves pure thoughts about God,

because they have, not Speech, that which forms in us the image of the Truth. We

have received the gift of Speech that we may not be as speechless animals in our

conduct, but that we may in our actions resemble God, the giver of Speech. How

great is Speech, a gift which came to make those who receive it like its Giver !

And because animals have not Speech they cannot be the likeness of our minds.

But because the mind has Speech, it is a great disgrace to it when it is not

clothed with the likeness of God ; it is a still more grievous shame when

animals resemble men, and men do not resemble God. But threefold is the torture

doubled when this intermediate (party between God and animals) forsakes the Good

above him and degrades himself from his natural rank to put on the likeness of

animals in his conduct.

| And a letter cannot speak. |

A letter, therefore, cannot demonstrate every matter about which a man is

seeking to ask questions, because the tongue of the [Ov. p. 23, 1. 2.] letter is

far away from it,—its tongue is the pen of the writer of it. Moreover, when the

letter speaks anything written in it, it takes to itself another tongue that the

letter may speak with it, (the letter) which silently speaks with two mute

tongues, one being the ink-pen, the other, the sight of the (reader's) eye. But

if we thus rejoice over a letter poor in treasures, how much more shall we

rejoice over a tongue which is near us, the lord and treasurer of the treasures

within !

| Yet I have written because I felt myself unworthy to

meet thy piety. |

But I had desired that instead of your seeing me in the characters of a

document, you might have seen me in the characters of the countenance ; and

instead of the writing of |iii my

letter thus seeing you, I had desired that my eyes instead of my writings might

see you. But because the sight of our face is not worthy of the pure gaze of

your eyes, behold you are gazing on the characters of our letter. But justly

pure writings have met your pure eyes ; not that I say that the pure is profaned

by the defiled, but it is not right that pure eyes should look at what is riot

pure. For even though the People had sanctified their bodies three days, (yet)

because they had not sanctified their hearts he did not allow them to approach

the holy Mountain, not that holiness would be profaned by those who were

defiled, but those who were defiled were not worthy to approach holiness. [Exod,

xix. 10 ff.] But by Moses, the holy one, who went up into the holy Mountain, God

gave an instance for the consolation of the pure and for the refutation of the

defiled, (showing) that all those who are holy like Moses are near holiness like

Moses. [Ov. p. 24.] For when one of the limbs of the body is satisfied all the

limbs receive a pledge of satisfaction, that they too will be satisfied together

with that one in the same manner. For by means of that body, too, in which our

Lord was raised, all bodies have received a pledge that they will be raised with

it in like manner.

| Discreet fear prevented me from visiting thee at thy

request. |

But, my brother, in that thou didst stir up our littleness to approach you,

know that if I wished I could come, but know, too, that if I could come I would

not wish to be deprived (of the opportunity). For I could come if I had no

intelligence ; but I have been unable to come because I had intelligence. In

(blissful) innocence I might have come on account of love, but (looking at the

matter) intelligently I was unable to come on account of fear.

| Not that I was overawed at the prospect of a

discussion. |

And whoever is steeped in love like a child is above fear ; and whoever! is

timorously subject to fear vain terror always tortures him. It helps athletes

too in a competition to be above fear through the encouragement of a good hope,

and not to fall under the sickly apprehensions which result from a timorous

habit of thought. Athletes perhaps (might) well fear because the victor is

crowned and the loser suffers shame, For they do not divide the victory between

the two of them.

| There would have been gain however it ended. |

But we ought not to fear a struggle in which failure is

|iv victory ; since when the teacher wins the

learner too is much helped. For helper and helped are both partakers in the

gain. If, then, we had come to teach there would have been a common victory as

Error would have been overwhelmed by our Truth. [Ov. p. 25. l. 3.] But if we had

been unable to teach, yet had been able to learn, there would have been a common

victory in that by your knowledge there would have been an end of ignorance. The

treasure of Him that enricheth every one is open before every one, since Grace

administers it, (Grace) that never restrains intelligent inquirers. If,

therefore, we had possessed something we could have bestowed it as givers, or if

we did not possess anything we could have received as inquirers. But if we had

not been able to give nor able even to receive, our coming could not have been

deprived of all good. For even if we could not have searched you out with our

mind yet we could have seen you with our eyes ; since we have no greater gift

than seeing you. [Ex. xxxiii. 18 ff.] But Moses testifies that while it was

granted to him to do everything like God, at last he abandoned everything and

prayed to see the Lord of all. For if the creatures of the Creator are thus

pleasant to look upon, how much more pleasant is their Creator to look upon ;

but because we have not an eye which is able to look upon His splendour, a mind

was given us which is able to contemplate His beauty. Man, therefore, is more

than his possessions, just as God is more excellent and more beautiful than His

creatures.

| In spite of my conscious inferiority I might have

given a little help: for all are mutually dependent. |

But know, my beloved, that if we had come, it would not have been possible

for us to have been real paupers such as receive everything, nor again for you

to have been complete givers, to give everything. One who lacks is not lacking

in all respects, lest he should be abased ; neither is he who is complete,

complete in every respect, lest he should exalt himself. But this lack has

arisen that completeness may be produced by it. For in that we need to give to

one another and receive from one another, the wants of all of us are filled up

by the abundance of all. [Ov. p. 26, 1. 7.] For as the wants of the limbs of the

body are filled up |v one by the other,

so also the inhabitants of the world fill up the common need from the common

abundance. Let us rejoice, therefore, in the need of all of us, for in this way

unity is produced for us all. For inasmuch as men are dependent on one another,

the high bend themselves down to the humble and are not ashamed, while the lowly

reach out towards the great and are not afraid. And also in the case of animals

we exercise great care over them on account of our dependence on them, and

obviously our need of everything binds us in love towards everything. O hated

Need ! yet much-loved unity is produced from it. Because countries are dependent

on one another, their dependence combines them as into a body ; and like the

limbs they give to one another and receive from one another. But these

arrangements of interdependence belong to one rich complete Being, Whose need is

this—to give to everything though He has no need to receive from anywhere. For

even what He is thought to receive from us, He takes it astutely from us

in His love that He may again give it to us manifold more as the rewarder. This

is that astuteness which ministers good things, and our craftiness which

ministers evil things should resemble it.

| I said above that I refrained from coming through

fear. Such fear even S. Peter experienced. |

But as regards that fear of which we spoke above, not only upon us weak ones

does the constraint of fear fall, but even upon the heroes and valiant

themselves. Nor have I said this in order to find comfort for our folly, but

that we might remind thy wisdom. For when Peter despised fear and was wishing to

walk upon the waters, although he was going (thither) on account of his love

which was making him run, yet he was nigh to sinking on account of fear which

fell upon him ; and the fear which was weaker than he on dry land, when it came

among the waves into a place in which it was strengthened became powerful

against him and overcame him. [Ov. p. 27, l. 13.] From this it is possible to

learn that when any one of all the desires in us is associated with an evil

habit which helps it, then that desire acquires power and conquers us. For fear

and love were weighed in the midst of the sea as in a balance, and fear turned

the scale and won ; and that Simon whose faith was lacking

|vi and rose in the balance was himself nigh to

sinking in the midst of the sea. And this type is a teacher for us, that is to

say, it is a fear-inspiring sign that all those whose good things fail and are

light when rightly weighed, are themselves nigh to sinking into evil. But if any

one say :—why is it necessary to frame illustrations of this kind, let him know

that this may not be harmful if we receive from everything some helpful lesson

for our weakness. [Ov. p. 28.] If, therefore, Peter was afraid of the waves,

though the Lord of the waves was holding his hand, how much more should weak

ones fear the waves of Controversy, which are much stronger than the waves of

the sea! For in the waves of the sea (only) bodies are drowned, but in the waves

of Investigation minds sink or are rescued.

| The Publican in the Parable was conscious of this

fear. |

But, again, that Publican also who was praying in the Temple was very

importunate about forgiveness, because he was much afraid of punishment. He was

in a state of fear and love ; he both verily loved the Merciful One on account

of His forgiveness, and he verily feared the Judge on account of His vengeance.

And though, on the one hand, he was praying in love because of his affection,

yet, on the other hand, because of his fear he would not dare to lift up his

eyes unto Heaven. And though Grace was urging him forward, his fear was unable

to cross boldly the limit of justice.

If the fear of the Publican who was justified knew its measure and did not

exalt itself to cross the limit, how can weakness dare to neglect the measure

and to cross the limit of propriety ? For this also (is said) that a man may

know the degree of his weakness and not exalt himself to a degree above his

power. I think that such a man cannot slip. For he does not run to a degree too

hard for him and so receive thence a fall. For without knowledge men run to

degrees too hard for them ; and before they go up pride urges them on, and after

they fall penitence of soul tortures them.

| On the other hand,the Lord gave a Parable of

unabashed importunity. |

But, again, indeed, I see that that importunity about which our Lord spake

was praised and enriched because its importunate nature ventured to cross the

limit of propriety ; for if it had been abashed and observed propriety, it would

have gone empty away, but because it was presumptuous and trampled down

|vii harmful modesty as with its

heels, [Ov. p. 29, l. 5.] it received more than it had asked. O Necessity, whose

importunate words enriched its destitution! For it does not aid necessity to be

subject to harmful modesty, but (it is aided) by its importunity being a good

instrument for (securing) good things.

| Better, therefore, is wholesome importunity, than a

barren scrupulosity about exact propriety. |

But if all these praises were bestowed on importunity, which opened closed

doors, and aroused those who were asleep in bed, and received more than was its

due, how must that indigence be censured which has not approached open doors nor

received help from the treasuries of the Rich One ! Better, therefore, is

he who is importunate about his aid than he who is ashamed and loses his aid.

For whoever observes proper modesty while he loses his aid, even the propriety

which he has observed is in that case subject to censure, and propriety has

become impropriety. And he that seeks after exact propriety at all times is

neglectful of sound propriety. For from the best wheat, if it shed not much

bran, fine flour cannot be made ; for unripe fruit is not palatable, and what is

over ripe loses flavour, or else its taste is pungent, or bad.

| The proper limits of Knowledge. |

For if we refine things much beyond what is proper, even the fine and the

pure are also rejected. For it is not right for us to cultivate Ignorance, or

deep Investigation, but Intelligence between-these-two-extremes, sound and true.

For by means of the two former a man surely misses his advantage. [Ov. p. 30, l.

3.] For by means of Ignorance a man cannot understand Knowledge, and by deep

Investigation a man cannot build on a sound foundation. For Ignorance is a veil

which does not permit one to see, and Investigation, which is continually

building and destroying, is a changeful wheel that knows not how to stand and be

at rest; and when it passes in its investigation over true things, it cannot

abide by them ; for it has unstable motions. When, therefore, it finds anything

it seeks, it does not retain its discovery, and is not rejoiced with the fruit

of its toil But if we inquire much into everything we are neglectful of the Lord

of everything, inasmuch as we desire to know all things like Him. And since our

Knowledge cannot know everything. |viii

we show our evil Will before Him Who knows all things. And while He is higher

than all in His Knowledge, the ignorant venture to assail the height of His

Knowledge. For if we are continually striving to comprehend things, by our

strife we desire to fence round the way of Truth and to confuse by our

Controversy things that are fair—not that those fair things are confused in

their own nature, but our weakness is confused by reason of the great things.

For we are not able completely to apprehend their greatness. For there is One

who is perfect in every respect, whose Knowledge penetrates completely through

all.

| It is not good for us to seek deep Knowledge : for

deep things are unknowable. See how Simplicity is better than

Cleverness. |

But it is not right for us to look at all things minutely, but rather

simply—not that our Knowledge is to be Ignorance; for even in the case of

something which a man does not do cleverly, if he does the thing with clever

discrimination then his lack of Cleverness is Cleverness. And if, by his

Knowledge he becomes an ignorant man so that he ignores those things which he

cannot know, even his Ignorance is great Knowledge. For because he knows that

they are not known, his Knowledge cannot be Ignorance. For he knows well

whatever he knows. But the mind in which many doubts spring up, destroying one

another, cannot do anything readily. For thoughts, vanquishing and vanquished,

are produced by it, and the waves which from all sides beat upon it, fix it in

doubt and inaction. [Ov. p. 31, l. 12.] But it is an advantage that the scale of

simplicity should outweigh in us the scale of wrangling-logic. For how many

times, in consequence of the clever and subtle thoughts which we have concerning

a matter, that very matter is delayed so as not to be accomplished! And consider

that in the case of those matters which keep the world alive, Simplicity

accomplishes them without many thoughts. For these matters succeed when a single

thought controls them, and they stand still when many thoughts rush in. For

there is only a single thought in Husbandry, that is (the thought) that in a

simple manner it should scatter the seed in the earth. But if other thoughts

occurred to it so that it pondered and reasoned as to whether the seed was

sprouting or not, or whether the earth would fail to produce it, or would

restore it again, then Husbandry could not sow. For morbid thoughts spring up

against a single |ix sound thought,

and weaken it. And because a thing is weakened, it cannot work like a sound

thing. For the soundness of a [Ov. p. 32.] thought like the soundness of a body

performs everything. And the husbandman who cannot plough with one ox cannot

plough with two thoughts. Just as it is useful to plough with two oxen, so it is

right to employ one healthy thought.

| Deep Investigation is to be avoided. |

Moreover, if the martyrs and confessors who have been crowned had approached

with double thoughts they could not have been crowned. For when our Freewill is

in a strait between keeping the commandment and breaking the commandment, it is

usually the case that it is seeking two reasonings destructive of one another,

so that by means of the. interpretation of one reasoning it may flee from the

pain of the other, that is to say, (it argues) in order that by a false excuse

it may cast away the burden of the commandment. Now, without wandering after

those things which are unnecessary, or omitting anything that is necessary, let

us say in brief and not at length, that if anything succeeds by means of a

single sound thought, its soundness is weakened by many thoughts. For if we

approach with polished wiles any matter which we ought to approach in a simple

way, then our intelligence becomes non-intelligence. For in the case of every

duty, whenever a man proceeds beyond what is its due, all the ingenuities which

he can devise about it, are foolish. So (too) in the case of any investigation

in which the investigator slips from its truth, all the discoveries he may make,

although his discoveries may be clever, are false. For everything which is

clever is not true ; but whatever is true is clever. And whatever is debated is

not deep, but whatever is said by God is subtle when it is believed. But there

is no subtlety equal to [Ov. p. 33.] this, that everything should be duly done

in its own way, and if it happen that what is to be done can be done simply, its

simplicity is subtlety. For it is all the more fitting that we should call this

simplicity subtlety in that it accomplishes helpful things without many

combinations and reasonings. For in that it does things easily it resembles

Deity, Who easily creates everything.

| The advantage of simple Knowledge can be seen in the

case of the husbandman. |

It is right, therefore, that we should investigate well the advantage of

things by an examination of them ; and if they are

|x judged by the investigators to be simple, there

are many things which are thought to be obviously unsuccessful, but their unseen

qualities achieve a great victory. For there is nothing that appears more simple

than this, that the husbandman should take and scatter in the earth the gathered

seeds which he holds in his hands. But, after a time, when it is seen that the

scattered seed has been gathered and has come with a multitude like a general

with his army, and that the seed which had been regarded as lost is found and

finds also other (seeds) with it, then a man marvels at the husbandman's

simplicity, which has become a fountain of cleverness. Therefore, with regard to

this very thing, hear on the other hand the opposite of it, that if a man spare

the gathered seed, so as not to scatter it, he is thought indeed to act

prudently in refraining from scattering. But when we see the husbandman's

scattered investment collected in the principal and interest, and the earth

rewarding him, then the intelligence which refrained from scattering is seen to

be [Ov. p. 34.] blindness, because it is deprived of (the chance of) gathering.

Therefore, it is not an advantage to us that we should always be led astray by

names, nor that we should be deceived by outward appearances.

| I considered the matter carefully before I decided

not to visit thee. |

For if, because I wisely discerned that it would not be right for me to

venture to come, I did not come for that reason, perhaps it would have been

better for me if I had not wisely discerned. For, perhaps, my coming to thee in

childlike and simple fashion would have met with success. But know again that if

I had come recklessly I would not have wished to come, because our coming would

have been indiscreet. For we should have had no fruit of intelligence. For

everything which is done indiscreetly belongs either to reckless habit, or blind

chance ; and it has no root in the mind of those who do it.

| In deciding, I was conscious of a free power of

Choice within me: the nature of Freewill. |

But if these two wise conclusions (namely) that I should come and that I

should not come, (both) belong to my Will, this is a single Will of which one

half does battle with the other half, and when it conquers and is conquered it

is crowned in both cases. This is a wonder, that though the Will is one, two

opinions which are not homogeneous are found in its homogeneity. And I know that

what I have said is so, but why (it is so) I am not

|xi able to demonstrate. For I wonder how that one

thing both enslaves it and is enslaved by it. But know that if this was not so

mankind would have no free power of Choice. For if Necessity makes us wish, we

have no power of Choice. And if, again, our Will is bound and has not the power

to will and not to will we have no Freewill. ["The Will is both

one and many."] And, therefore, necessity thus demands that there should

be a single thing, and though it is a single thing, when that single thing wills

to be two it is easy for it, and when again it wills to be one or many it is a

simple matter for it. For in a single day there are produced in us a great

number of Volitions which destroy each other. [Ov. p. 35, l. 5.] This Will is a

root and parent; it is both one and many. This Will brings forth sweet and

bitter fruit. O free Root with power over its fruit! For if it wills it makes

its fruits bitter, and if it wills it makes its products sweet. For God to Whom

nothing is difficult has created in us something which is difficult to explain,

and that is, Freewill. And though this (Will) is one, yet there are two opinions

in it, that of willing and that of being unwilling ; so that when half of it

struggles with and conquers the other half, then the whole of it is crowned by

the whole of it. For this is an unspeakable wonder, how, though the Will is one,

half of it rebels against the Law and half of it is subject to the Law. For, lo,

there are in it two opinions contending together, for part of the Will desires

that Evil should be done, and again, part of it uses restraint and guards

against Evil being done. And how on the one hand has the Will not been

transformed by that part of it which desires evil things that it may become like

its part which desires evil things ? and how again (on the other hand) has the

Will not been converted by that part of it which loves good things, that the

whole of it may become good like the part of it which loves good things ? But if

both these parts can be converted to Good or Evil, what shall we call them ?

That we should call them Evil (is impossible, for) they can be good,—that we

should call them good (is impossible, for) they can be bad. [Ov. p. 36.] And

though these two can be a single thing, yet except they are divided and are two

there can be no struggle between them. This is a wonder which we are unable to

speak of, and yet we cannot be silent about it. For we know

|xii that a single Will possessed of many

conclusions exists in us. But since the Root is one we do not understand how

part of the thought is sweet, and part of it bitter, even if it does not

completely escape our notice. And how, on the one hand, is that bitterness

swallowed up by that sweet thing so as to become pleasant like it ? And how

again when it (i.e., the sweet thing) has been swallowed up is it mixed

with that bitter thing so as to become bitter like it ? And again, how when

these two frames of mind have been swallowed by one another, and have become one

thing affectionately, are they again separated from one another and stand one

against the other like enemies ? For where was that Mind before we sinned that

brings us to penitence after sins ? And how is that Mind turned to penitence

after adultery, which was raging before adultery ? These are frames of mind

which are like leaven to one another, so that they change one another and are

changed by one another. But here our Truth has conquered the (false) Teachings

and bound them so that none of them can bear investigation.

| This Discourse is meant for friends. |

But if any one wishes to investigate some of the Teachings (in question) let

him know that we have not been called at present to struggle with enemies, but

to speak with friends. But when the statement (intended) for friends is

finished, then our belief will show a proof of its power in a contest also. But

it is easy for every man to perceive what I have said, because there are in

every one two Minds, [Ov. p. 37.] which are engaged in a struggle one against

the other, and between them stands the Law of God, holding the crown and the

punishment, in order that when there is victory it may offer the crown, and when

failure appears it may inflict punishment.

| False views about the origin of Evil make the Law an

absurdity, or make Good akin to Evil. |

But if the Evil which is in us is evil, and cannot become good, and if also

the Good in us is good, and cannot become evil (then) these good and evil

promises which the Law makes are superfluous. For whom will the Rewarder

crown—one who is victorious by his Nature and cannot fail ? Or whom, again, will

the Avenger blame—that Nature which fails and cannot conquer ? But if that good

thing which is in us is obedient to |xiii

something evil, how can we call that Good, seeing that it has a close

relationship to Evil ? For by means of that thing whereby it becomes obedient to

Evil its kinship with Evil is perceived. For that Evil would not be able to draw

it to itself if it were not that its lump had an affinity to the leaven of Evil.

See therefore, also, that what they call a good Nature is, in virtue of what it

is, convicted of being an evil Nature; inasmuch as it has an evil Will which is

drawn away after Evil. But inasmuch as it has an evil Will, all Evil things had

a tendency towards it. [The evil Will is the root of Evil.]

For there is nothing more evil than an evil Will. For that is the root of evil

things. For when there is no evil free Will, then evil things come to an end.

For the deadly sword cannot kill apart from the evil Will of its holder. [Ov. p.

38.]But see, already when we have not advanced to the contest (even) before the

contest, the enemies of the Truth have been conquered beforehand.

| The Will is its own explanation. |

And if any one ask, what then is this Will ? we must tell him that the real

truth about it is that it is the power of Free-choice. And because it is not

right to scorn a good learner, let us now like those who hasten and pass on

throw him a word, that is to say, one of the words of Truth. For, even from a

single word of Truth, great faith dawns in a sound and wise hearer ; just as a

great flame is produced by a small coal. For if a single one of a few coals of

fire is sufficient to make scars on the body, one of the words of Truth, also,

is not too weak to clean away the plague spots of Error from the soul. If,

therefore, any one asks, "What is this Will, for though it is one thing, part of

it is good, and part of it evil ?" we shall tell him that it is because it is a

Will. And if he asks again, we shall tell him that it is a thing endowed with

independence. And if he still continues to indulge in folly, we shall tell him

that it is Freewill. And if he is not convinced this unteachableness of his

teaches that because there is Free-will he does not wish to be taught. But if he

is convinced when they say to him that there is no Freewill, it is truly

wonderful that in the annulling of his Freewill, his Freewill is proved, that is

to say, by his being in a desperate state. [The very denial of

Freewill proves that it exists.] And the matter is as if some eloquent

person wished to harangue and to prove that men have no power of Speech. And

that is great madness; |xiv for he

says there is no power of Speech when he uses the power of Speech. For his power

of Speech refutes him, for by means [Ov. p. 39.] of Speech he seeks to prove

that there is no power of Speech. When Freewill, too, has gone to hide itself in

a discussion and to show by argument that it does not exist, then is it with

more certainty caught and seen to exist. For if there were no Freewill, there

would be no controversy and no persuasion. But if Freewill becomes more evident

when it hides itself, and when it denies (its own existence) it is the more

refuted, then when it shows itself it is made as clear as the sun.

| The Will is not enslaved, but is the Image of God. |

And why does Freewill wish to deny its power and to profess to be enslaved

when the yoke of lordship is not placed upon it ? For it is not of the race of

enslaved reptiles, nor of the family of enslaved cattle, but of the race of a

King and of the sons of Kings who alone among all creatures, were created in the

image of God. For see every one is ashamed of the name of slavery and denies it.

And if a slave goes to a country where men know him not, and there becomes rich,

it may be that, although he is a slave and of servile origin, he may be

compelled to say there that lie is sprung from a free race and from the stock of

kings. And this is wonderful that, while slaves deny their slavery, yet the

Freewill of fools denies its own self. And see, if men give the name of slave to

him who says that there is no Freewill, he is displeased and becomes angry, and

begins to declare the Freedom of his family. Now, how does such a person on the

one hand deny Freewill, and on the other acknowledge it ? And on the one hand

hate literal slavery, and (on the other) acknowledge spiritual slavery ? If he

chose with intelligence and weighed the matter soundly it would be right for him

to acknowledge that (principle) that he might not be deprived of the mind's free

power of Choice. [Ov. p. 40.] And here he is exposed who blasphemes very

wickedly against the Good One, the Giver of Freewill, Who made the earth and

everything in it subject to its dominion.

| Freewill is denied by those who wish to blame God for

their failures. |

But there is no man who has gone down and brought up a crown with great toil

from the hard struggle, and (then) says that there is no Freewill, lest the

reward of his toil and the glory of his crown should be lost. The man who has

failed says there |xv is no Freewill

that he may hide the grievous failure of his feeble Will. If thou seest a man

who says there is no Freewill, know that his Freewill has not conducted itself

aright. The sinner who confesses there is Freewill may perhaps find mercy,

because he has confessed that his follies are his own ; but whoever denies that

there is Freewill utters a great blasphemy in that he hastens to ascribe his

vices to God ; and seeks to free himself from blame and Satan from reproach in,

order that all the blame may rest with God—God forbid that this should be ! But

if he is intelligent he ought not to think that a being endowed with power over

itself is similar to a thing which is bound in its Nature. [The

mystery of the Will is a part of a wider mystery.] And, moreover, it

would not be right for any one, after he has heard that the Will . . . to ask

(and say), 'But what, again is the Will ?' Does he know everything, and has this

(alone) escaped his knowledge, or does he know nothing at all since he cannot

know even this ? But if he knows what 'a bound Nature' is, he can know what an

unconstrained Will is, but that which is unconstrained cannot become

constrained, because it is not subject to constraint. But in what is it

unconstrained except in that it has (the power) to will and not to will?

| The power of Freewill is obvious but unspeakably

difficult to explain. |

And if he is unwilling to be convinced in this way, it is because the power

of his Freewill is so great, and our mouth is unable to do it full justice ; our

weak mouth has confessed that it is unable to state its unconstrained Will. For

it is a Freewill which subjects even God to Investigation and rebuke, on account

of its unconstrained nature. It ventured to bring up all this because it desired

to speak about that which is unspeakable. [Ov. p. 41, l. 5.] But that (Freewill)

which has ventured to make statements concerning God, itself is not able to

state its own nature perfectly. But concerning this, also, we say to any one who

asks that this is a marvel which it is very easy for us to perceive, but it is

very difficult to give a proof of it. [But it is impossible to

explain anything completely.] But this is not so only in this matter, but

it is the same with everything. For whatever exists may be discussed without

being searched out; it can be known that the thing exists, but it is not

possible to search out how it exists. For see that we can perceive

|xvi everything, but we cannot

completely search out anything at all ; and we perceive great things, but we

cannot search out perfectly even worthless things. [Let us thank

God that our Knowledge of things is limited.] But thanks be to Him Who

has allowed us to know the external side of things in order that we may learn

how we excel, but He has not allowed us to know their (inward) secret that we

might understand how we are lacking. He has allowed us, therefore, to know and

not to know that by means of what can be known, our childish nature might be

educated, and that our boldness might be restrained by those things which cannot

be known. Therefore, He has not permitted us to know, not that we may be

ignorant, but that our Ignorance may be a hedge for our Knowledge. [Knowing

that our powers of knowing are so limited we can avoid vain and weary searching.]

For see how we wish to know even the height of heaven and the breadth of the

earth, but we cannot know ; and because we cannot know we are thus restrained

from toiling. Therefore, our Ignorance is found to be a boundary for our

Knowledge, and our want of Knowledge (lit. simpleness) continually controls the

impetuosity of our boldness. For when a man knows that he cannot measure a

spring of water, by the very fact that he cannot, he is prevented from drawing

out what is inexhaustible. [Ov. p. 42, l. 5.] And by this experience it is seen

that our weakness is a wall in the face of our boldness. Thus, too, when we know

that we cannot know, we cease to investigate. For if, when we know little, the

impetuosity of boldness carries us on and proceeds to those things which may not

be known, who is there who will not give thanks to Him. Who has restrained us

from this wearisomeness, even if we do not wish to remain within the just

boundary within which He has set us ? Our Ignorance, therefore, is a bridle to

our Knowledge. [Yet we are not to be ignorant, but to seek after

practical Knowledge.] And from these instances it does not follow

that the All-knower wished to make us ignorant, but He placed our Knowledge

under a helpful guardian ; and better is the small Knowledge which knows the

small range of Ignorance than the great Knowledge which has not recognized its

limits ; and better is the weak man who carries about something that is

necessary for his life than the arrogant strong man who burdens himself with

great stones which cause his destruction. [Our chief Knowledge is

to know what subjects can never be known.] But our chief Knowledge is

(just) this—to know that we do not know |xvii

anything. For if we know that we do not know, then we conquer Error by our

Knowledge. For when we know that everything that exists is either known or not

known, thereby we acquire the true Knowledge. For whoever thinks he can know

everything, falls short of the Knowledge of everything. For by means of his

Knowledge he has gained for himself Ignorance. But whoever knows that he cannot

know, from Ignorance Knowledge accrues to such a one. [Ov. p. 43.] For in virtue

of the fact that he knows that he cannot know, he is enabled to know, that is to

say, (he knows) something which profits him.

| No external force compelled my Will when

deciding not to come to see thee. |

If, therefore, as I said above, though the Will is one, part of it compels

and part of it is compelled, by whom was I compelled not to come except by my

own Will ? O that some unknown external

Constraint had opposed me ! For perhaps with the whole of my being I would have

contended against the whole of that (Constraint) and been victorious. (O that it

had been thus), and that an inward Constraint had not opposed me, (a Constraint)

of which I know not how to give an account ! For I am not able to state how part

of me contends with another part ; in virtue of being what I am, I conquer, and

am conquered continually.

| The heretical Teaching says that the Will is a

Mixture. |

But we are not stating the case as the Heresies state it. For they say that

Constituents of Good and Evil are mingled together in us, and "these

Constituents conquer one another, and are conquered by one another." But

although Error is able to deck out what is false, the furnace of Truth is able

to expose it. For we say that free Volitions conquer one another, and are

conquered by one another ; for this is the Freewill which the voice of the Law

can transform.

| Consequences of the denial of Freewill. |

And if they say that if Freewill comes from God, then the good and evil

impulses which belong to it are from God ; by saying this, what do they wish to

say ? Do they wish to affirm that there is no Freewill ? And if they deny

Freewill what can they believe ? [Ov. p. 44.]For if they deny Freewill the Law

and Teaching are of no use ; and so let books and laws be rolled up and let

judges rise from their thrones, and let teachers cease to

|xviii teach! let prophets and apostles resign their

office! Why have they vainly laboured to preach ? Or what was the reason of the

coming of the Lord of them all into the world ?

| Freewill and the teaching about the Constituents are

incom patible. |

But if they profess belief in Freewill—which is actually what they

profess—that Freewill which they profess to believe in compels them to deny that

Evil which they believe in. For both of them cannot stand. For either our Will

sins, and (at other times) is proved to be righteous, and for this reason we

have Freewill; or if the Constituents of Good and Evil stir in the Will, then it

is a Constituent which overcomes, and is overcome, and not the Will.

| Freewill means Freewill not a 'bound Nature.' |

But if any one says that everything which stirs in our Freewill does not

belong to Freewill, by his Freewill he is making preposterous statements about

Freewill. For how does he call that Freewill when he goes on to bind it so that

it is not Freewill. For the name of Freewill stands for itself; for it is free

and not a slave, being independent and not enslaved, loose, not bound, a Will,

not a Nature. And just as when any one speaks of Fire, its heat is declared by

the word, and by the word 'Snow,' its coolness is called to mind, so by the word

'Freewill' its independence is perceived. But if any one says that the impulses

that stir in it do not belong to Freewill he is desiring to call Freewill a

'bound Nature,' when the word does not suit a Nature. And he is found not to

perceive what Freewill is, and he uses its name rashly and foolishly without

being acquainted with its force. [Ov. p. 45.] For either let him deny it, and

then he is refuted by its working, or if he confesses it, his organs contend one

against the other ; for he denies with his mouth what he confesses with his

tongue.

| The Law of God presupposes Freewill. |

For the Giver of Freewill is not so confused (in mind) as this man who is

divided (against himself) part against part, that He should become involved in a

struggle with His nature. For He gave us Freewill which, by His permission,

receives good and evil impulses, and He furthermore ordained a Law for it that

it should not do overtly those Evils which by His permission stir invisibly in

it. And let us inquire a little. Either though He may have had the means to give

us Freewill, He did not wish to give it, though He may have been able to give

it, or He may |xix not have had the

means to give, and on this account He was unable to give it. And how was He Who

was unable to give freewill able to give a Law when there was no Freewill ? But

if He gave the Law, the righteousness which is in His Law reproves our Freewill,

for He rewards it according to its works.

| The diversity among men proves that Freewill exists. |

And if there is no Freewill, does not this Controversy in which we are

involved concerning Freewill, bear witness that we have Freewill ? For a 'bound

Nature' could not utter all these various matters controversially. For if all

mankind were alike saying one thing or doing one thing, perhaps there would be

an opportunity to make the mistake (of thinking) that there is no Freewill. But

if even the Freewill of a single man undergoes many variations in a single day